The intersection of racism, homophobia, and sexism is one where many collisions occur, but Wade Davis has positioned himself there, directing traffic and trying to detoxify toxic masculinity.

For four years, his position was defensive back in the NFL, an especially tough one to play as a closeted gay man.

Now, Davis speaks to men about gender inequality and masculinity at companies like Google and Netflix. He’s also the NFL’s first consultant on LGBTQ inclusion.

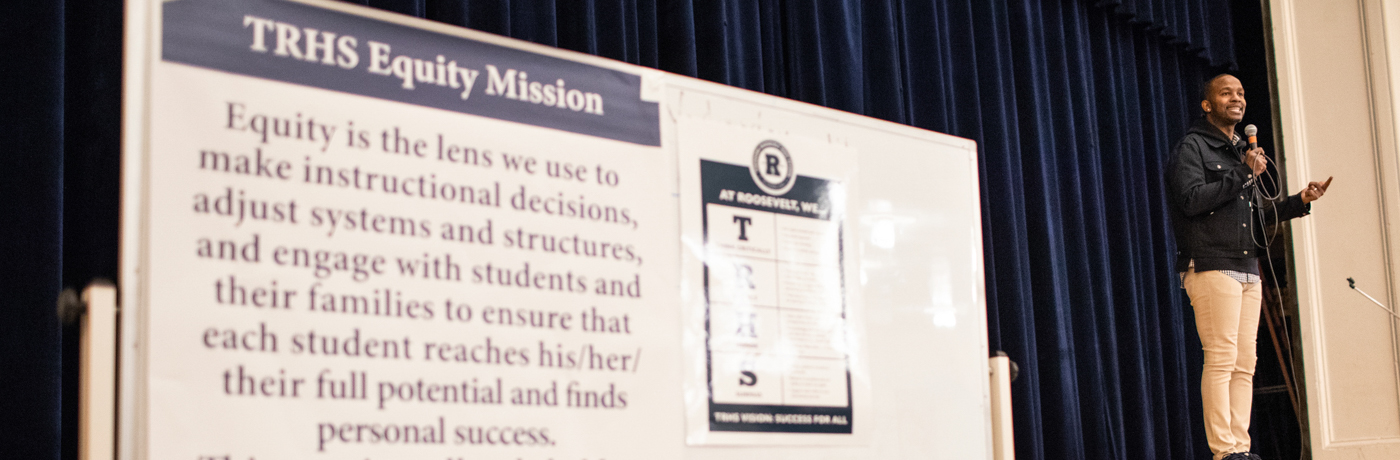

Wednesday morning he spoke to students at Roosevelt High School.

Nicole Ellis is the Equity Coach at Roosevelt. ”We are working to build an equitable school environment that allows each student to find their personal success,” she said. Davis was there to assist in that effort.

When he started to confide about the awakenings of his own sexuality during high school and the self-loathing he experienced, a murmur rippled through the auditorium. Not a disrespectful one of inattention, but a nervous one of discomfort. When he finished, the audience rose for a standing ovation.

“I was a mama’s boy,” Davis said, “and a church boy. But I was also a good athlete. I discovered my talent for football playing ‘Smear the Queer.’ It was much later that I discovered the courage it took to actually be the queer.”

Davis recounted how he went out of his way to bully the only openly gay boy in his high school. And how he got himself a trophy girlfriend in college, desperate to conceal his true sexual self from others and deny it to himself.

“When I made it to the NFL, I was living out my dream, yet I was deeply miserable,” he said. “I hated myself for being gay.”

He couldn’t reconcile that people sought his autograph, but only because of his macho disguise.

A career-ending injury began Davis’s search for self-acceptance. He moved to New York City and discovered a website for gay athletes that introduced him to a supportive community. By 2012, he was out and tabbed by President Obama to be a liaison to the LGBTQ community.

“Being accepted for the first time for who I actually was led me to self-acceptance,” Davis said. “And gradually I learned to love myself.”

Any uneasiness in the auditorium at the outset was gone by the time Davis opened things up for some Q&A after his talk. One questioner wondered if he’d ever been included in the popular Maddon NFL video game (Yes, Davis said, in 2006-07). But others sought advice about coming out to parents and how to counsel siblings.

Davis cited Maya Angelou’s distinction between bravado, which masculine stereotypes highlight, and bravery, which is what it takes to be different when you know you’ll be persecuted for it. There’s too much of the former. The latter is always in short supply.

“We have to learn to unlearn our biases by owning them,” he said. “Imagine being uncomfortable with the notion of someone loving someone else.”

Loving, he discovered, takes practice, just like football. The important difference is that you can do it for the rest of your life.

Principal Financial, Wells Fargo, Bankers Trust, Veridian Credit Union and Drake University jointly sponsored Davis’s appearance.