Last year six schools piloted a districtwide transition to the Schools for Rigor curriculum model. North High School along with Findley, Perkins, Weeks, Howe and Lovejoy elementary schools blazed a trail that leads from traditionally teacher-centric classrooms to dynamic student-centric ones.

This year an additional 16 schools begin the journey: Capitol View, Edmunds, Garton, Jefferson, Madison, McKinley, Monroe, Morris, Phillips, Samuelson, Willard and Windsor elementary schools; Harding, Hiatt and Hoyt middle schools, and Lincoln High School.

Schools for Rigor is a direct result of the district’s selection by the Wallace Foundation in 2014 for participation in a major effort to improve training and support for school principals, enabling them to spend more time coaching their staffs to transition from lecturers to facilitators.

Schools that make up the Year Two cohort are in the process of conducting RigorWalks with teams of district administrators and consultants from curriculum developer Learning Services International, like doctors making rounds with medical students.

According to LSI, the RigorWalk emphasizes these focus points:

- Ascertaining and improving the ability of the principal as an instructional leader

- Identifying and removing barriers to creating rigorous classrooms and subgroup achievement

- Improving overall student achievement

- Providing an objective third-party perspective

- Establishing a baseline for trend analysis

Thursday morning a team of observers met at Hoyt, led by Corey Harris, the district’s Director of Middle Schools and Executive Director of Secondary Schools Tim Schott. The day began with a “focus group” that included Hoyt principal Deb Markert and her building leadership team in addition to Harris and Schott.

After discussing what kinds of indicators to watch for, the group toured a sampling of classrooms.

“Remember, we are looking at a system,” Harris told the group before they entered, “not individual teachers.”

In a science class the visitors scribbled on their data rubric sheets while the students completed a start-of-the-year knowledge survey. It was so quiet you could hear pencils making their marks.

But is that necessarily a good thing?

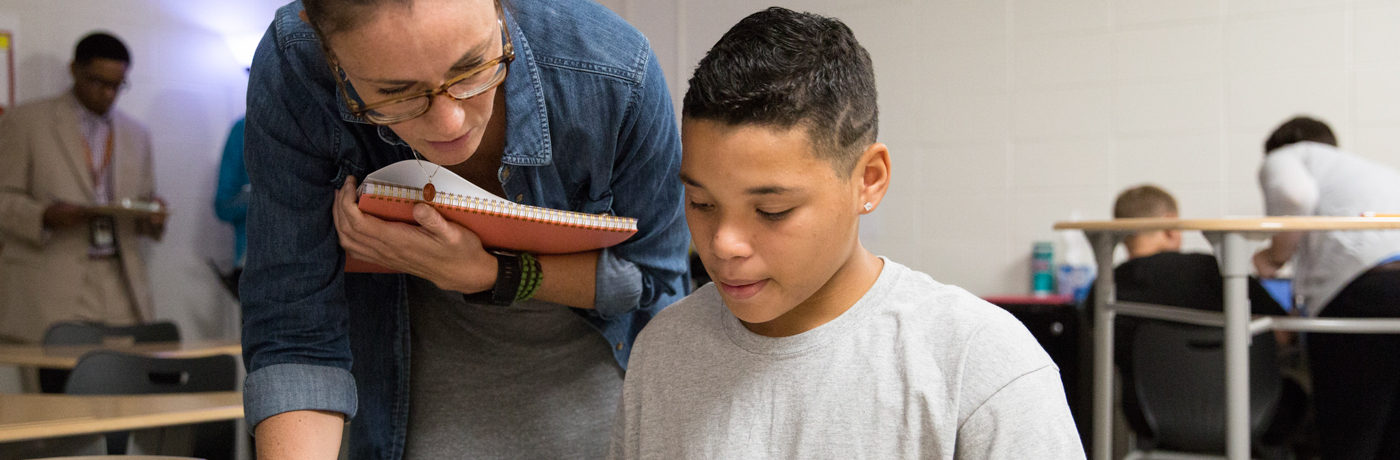

Schools for Rigor challenges educators to reconsider what learning and achievement look and sound like while they’re happening.

After the first round of three classroom drop-ins, the team adjourned to a hallway to compare notes.

“How were the learning conditions?” Harris asked. Good, in each case, everyone agreed.

“Who’s doing most of the heavy lifting?” was the follow-up. Again, agreement – that the teachers were in clear control. But in that environment, what is the evidence of success? The students appeared to be “compliant,” but were they fully engaged?

Sometimes the trick isn’t to reteach the teachers, but simply to give them permission to take chances and follow hunches that tap into students’ natural tendencies to learn from one another. Talking heads are better gauges of understanding than nodding ones.

“Teachers shouldn’t fear loss of control,” said Markert. “We will coach them to a different understanding of their objectives.”

Daily learning targets are a key concept in all of this. They are to be clearly articulated and posted so everyone knows where they’re aiming. And the aim must always be high. “How much of what we see results from where we set our expectations for students?” Harris asked the Hoyt leaders to consider.

A RigorWalk sounds like it would be exhausting but it’s not that at all. It’s enlightening, really, and a good exercise – one that’s leading to a school district fit enough to call itself the model for urban education.