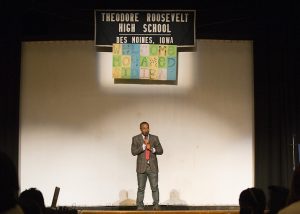

Former Boy Soldier Shares Story with Roosevelt Students

Mohamed Sidibay, a former boy soldier from Sierra Leone, shared his story with students at Roosevelt High School.

Roosevelt High School 9th graders have been reading A Long Way Gone: Memoirs of a Boy Soldier by Ishmael Beah. Thursday afternoon that bestseller came to life when Mohamed Sidibay traveled all the way from Sierra Leone, West Africa by way of George Washington University in Washington D.C. to speak with them about his own parallel experiences when he was forced to become a child combatant in his country’s civil war.

English teacher Emily Bollinger was awarded a One Classroom at a Time grant earlier this year by Banker’s Trust and ABC5 which she used to defray part of the cost of bringing Mohamed to Roosevelt. To make up the difference she established a GoFundMe account and the Roosevelt Foundation and her excited, engaged students took it from there.

This is what you call going the extra five thousand miles.

But that’s Bollinger’s style. In 2008 when her classes were reading work by the famed Freedom Writers she arranged for some of the authors to visit Roosevelt and tell their remarkable stories about overcoming the long odds against them growing up on the mean streets of southern California.

Those were powerful first person accounts. But Sidibay’s story was at another level.

He is 22 and will graduate from GWU in May. When he was five and liked to climb mango trees during games of hide and seek or play soccer at the beach the rebels came to his village. The intervening years were an unimaginable Act I of horror followed by Act II which includes the incredible soliloquy of survival that was told on the auditorium stage at Roosevelt.

“Adulthood began for me at five,” Sidibay said with blunt force. And it was terrifying.

First his family was killed. Mohamed was spared only to be absorbed into the ranks of the brutal rebel forces. He was issued an AK47, a devastating weapon that recoils so gently even a child can wield one. The young conscripts were blindfolded and made to fire at unseen targets. When the blindfolds were removed the novice and unwitting firing squad “saw the blood draining out of the people we had shot.”

Unwavering and remarkably vivid, Mohamed’s story included recollections of awakening to, “the stench breath from cheap liquor of my captor,” the ruthless man named Rambobot (you can guess his nickname) who’d killed Moahmed’s parents and siblings and told him “I am your commander and we are family now.”

He tried to run away and was stopped by a river he couldn’t cross because he couldn’t swim. Recaptured, he expected the “bullet to the head” that was understood as a routine consequence of resistance.

“When children run away they usually go to their rooms and lock the door, right?” he said. “A few hours later the parents come with cookies and all is well again.” Instead of cookies, and instead of being executed, Mohamed was tortured as an example to deter others from escape. He was beaten and burned with melting plastic. He bears scars that he explains to his friends at college in ways that jibe with the life of a “kid from New Jersey that I sometimes wish I really was.”

The boy soldiers were turned into spies and sent on missions that amounted to undercover reconnaissance in villages that were later attacked by their group which went by the name “No Living Thing.”

The older men placed bets on the gender of pregnant women’s babies and cut open their wombs to decide the wagers. “They forced me to hold my hand over a woman’s mouth who was carrying twins; a boy and a girl,” Mohamed recalled. “One of the men laughed and said at least he hadn’t lost any money.”

When the fighting spread from the villages to the capital city of Freetown the rebels were pushed back. Many of their leaders were killed and their subordinates didn’t have the same bloodlust.

“You hear people say things like the UN stopped the war,” Mohamed said, “but the UN, we know, is always fashionably late; never on time for anything.”

In the power vacuum Mohamed was rescued from the rebels by an Italian priest and eventually convinced to lend himself to a documentary film about the boy soldiers that was made when he was 10. That began the telling of his story that might last for the rest of his life.

Forced to kill or be killed as a child he wants to be a peacemaker. Already he is a Youth Ambassador for the UN in hopes that he can make it as punctual as it is well-intended.

When Mohamed arrived in America he was 14. He hopped in a cab at JFK airport and told the cabbie to head for the only place in New York City he’d heard of – Times Square. He only had $40 in his pocket but no worries; when he looked in the front seat the meter said $2.50. Who knew it kept running? “Half an hour later when we got to Times Square I gave the driver $4 and told him to keep the change,” Mohamed said, smiling.

Despite all that he saw and was made to do as a small child there stood a young man able to laugh at his own naivete. The happy ending is that he still has any.