Acholi to Zapotec: the Size and Scope of ELL in Des Moines

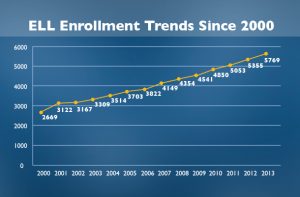

When Vinh Nguyen took over the district’s English Language Learner (ELL) program a decade ago it had already grown from about 275 students at its inception in 1975 to more than 2,500.

But according to School Board Vice-Chair Dick Murphy – a long-time educator who has worked closely with Iowa’s refugee community – it was in chaos bureaucratically. Data on how many students from how many countries spoke how many languages and were at what levels of English proficiency were hard to come by until Nguyen dug into the job.

Since then the ELL population has doubled to nearly 5,100, a number that represents more than the total number of students in all but 15 of Iowa’s 351 school districts. When students who have either transitioned out of the program or waived participation are factored in, the total rises to approximately 6,500 students in the district who come from homes where English is not spoken, a figure that represents roughly 20% of all DMPS students.

When the program began it was in response to an influx of refugees after Saigon fell at the end of the Viet Nam War. Nguyen was one of them. Now DMPS is a veritable Ellis Island, serving students who come to school speaking more than 80 languages, from Acholi to Zapotec. In many cases the district is absorbing refugees who are not yet literate in their native tongue and have never attended any sort of school anywhere. An already daunting task becomes even tougher when there aren’t language skills to transfer to English as the second language. Outreach workers can’t even be identified in the community who speak some of the dialects now represented in the district.

But the ELL corps of 86 teachers (that’s a 60:1 student/teacher ratio), 44 bilingual outreach workers, three administrators and three support staff deployed at five high schools, seven middle schools, 28 elementary schools and three Intensive Language Centers is accomplishing its extremely daunting task. Still, in another demonstration of the principle that no good deed goes unpunished, DMPS suffers for it under the arbitrary provisions of No Child Left Behind (NCLB) which holds ELL students to the same standards of proficiency on standardized tests as kids who’ve been speaking English all of their lives.

According to Nguyen, it now takes approximately six years in the ELL program for a student to achieve English proficiency and exit into mainstream curricula. Yet the state’s weighted funding formula of an extra .22 per ELL student only lasts for four years.

While the ELL population has been doubling in the last ten years the total DMPS enrollment has remained fairly constant. So a subgroup that used to be about 8% of the total is now about 16%. The district is home to roughly a quarter of Iowa’s entire ELL student population.

Murphy says Des Moines should be looking to hire as many teachers as possible with ELL endorsements among their credentials so the district’s expanding ELL cohort can be spread more evenly district-wide. But there aren’t enough of them to go around. Some suggest an increased emphasis on ELL should be factored into the revamped teacher training element of Governor Branstad’s education reform proposal along with increased funding that aligns with the realities of educating ELL kids.

To find out more about the ELL program at DMPS, click here.

On this same topic, view a Classroom Connections interview with Vinh Nguyen: